Moira Hayes, AMY, photography, plexiglas and vinyl, 22 x 30”, 2025.

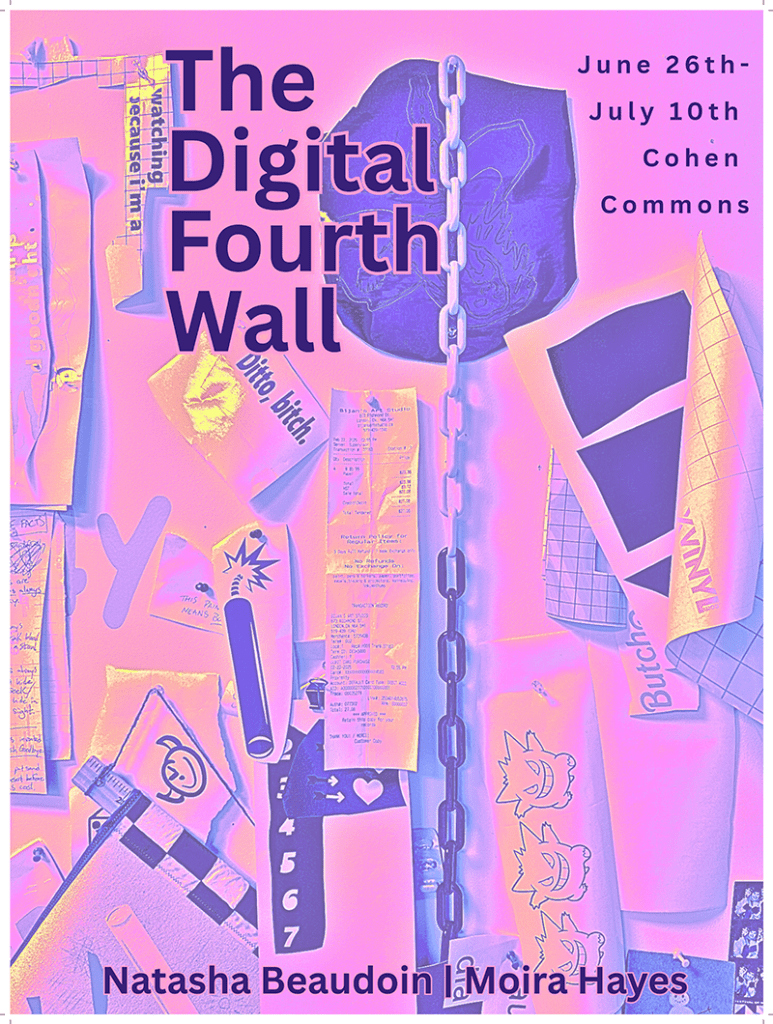

The Digital Fourth Wall is on view in the Cohen Commons, John Labatt Visual Arts Centre, from June 26 – July 10, 2025. The exhibition combines the work of Western University MFA candidates Natasha Beaudoin and Moira Hayes. Each artist studies the evolving Gen Z culture that emerges online and penetrates the real, offline world. Beaudoin and Hayes’ work meets at the intersection of reality and this generational view through a screen.

Each artist presents a series of portraits, the traditional media but always with a twist. Through portraiture, the subjects are in direct contact with the fourth wall, be that at a safe distance or uncomfortably close. The scrutiny that exists in the separation of subject and viewer leaves space for the formation of narratives, ultimately providing a different interpretation for any audience.

This conversation took place on May 27, 2025, behind the John Labatt Visual Arts Centre at Western University. In the shade of the trees beside the Antler River (the Thames River), we sat next to the water, with birds and bugs flying about.

KEYWORDS

The devil, cultural anxieties, social media, Gen Z, techno tenebrism, digital dependency, narrative strategy, breaking the fourth wall, queerness, femininity, materiality, installation effect, and critique.

Natasha Beaudoin

Cool. Okay, is it on? Yeah, it’s on. Okay, hi, Moira, hey.

Moira Hayes

Hi Natasha.

Natasha Beaudoin

Here is my first question:

You have mentioned in your proposed thesis creating a ‘suitable devil’ for current times. What qualities or cultural anxieties do you think the contemporary devil needs to embody, and why now?

Moira Hayes

Great question. I think the Now we’re currently situated in is quite unique for a lot of reasons. The biggest reason is because we’re post a global pandemic, and this has changed how we approach social interaction and communication, especially through the many different lenses of social media. There have never been so many ways to receive information.

I think a suitable devil for today needs to reflect all of these events and changes. [The devil] needs to adapt for younger people, like Generation Z and Generation Alpha, and in some respects younger Millennials, because they are what’s going forward. They are the future.

So, if the devil is traditionally seen as the embodiment of evil, and everything is new and different, then evil must be new and different too. It kind of goes in a circle; if we establish what the devil could be now, then we’ve established what evil could be now, and then we can try to understand it.

Let’s talk about how your work looks:

You call your style Techno Tenebrism, a natural progression from Caravaggio’s classical tenebrism and Rómulo Celdrán’s digital tenebrism, but your work is set apart because the characteristic dramatic light comes from you, the painter, when a reference photo is taken with camera flash. How does this shift of directional light function for the viewer? And is it meant to be narrative?

Natasha Beaudoin, Alex, Oil and AB crystals on Canvas, 24×36, 2024.

Natasha Beaudoin

I’m borrowing from Caravaggio’s tenebrism. So, he uses candlelight to create a sense of contrast and drama. It’s supposed to be enlightenment from God coming in. I try to take that sense of embodiment into a different facet, where the light is now artificially created, either from a screen, a tablet, or even from a plain LED light.

This glow is to show the separation between in-person and digital presence. So, kind of another [state of] being, you could say. And this relationship is meant to mediate the life that I have where presence and intimacy are separated by a flash, and you could read it as a narrative.

A lot of times, these images are placed together to show a whole scene of a specific time and place, not just one canvas on its own. There [needs to be] a series to paint the whole picture. Instead of one grand painting with multiple figures, its individual people set in place and time.

The light is also literal and symbolic. It emanates the natural need for connection: it’s me longing for my friends as they’re not physically present, so I must paint them [as a means] to bring them into my space. This is meant to comment on our digital dependency as well, that we require the use of technology to maintain the relationships we have. And then this action is narrative, because it’s a story of the relationship with the person that I’m capturing.

I specifically use different tools to show that, usually in a way where I feel it is fitting. For example, for my friends who are in fine art, I specifically use flash photography because I know they know how to pose for portraits, so I need to stun them. But for people who are like, say my partner, Elliot, [while speaking online] if I take a screenshot of him in the midst of talking, he has no time to pose or think, this is very natural to him.

Moira Hayes

All right.

Natasha Beaudoin

I’ll go back to you. Moira.

Moira Hayes

Yes, please.

Natasha Beaudoin

All right. My second question:

You reference television shows like The Wilds (2020), Yellowjackets (2021), as well as movies I Saw the TV Glow (2024) and Bottoms (2023) for their fourth wall breaking techniques. What role does this narrative strategy play in your understanding of the devil in the 2020s?

Moira Hayes

I find these pieces of media really important to how I’m studying the evils we face in the 2020s. The way I’m studying them and how I’m approaching the previous notions of the devil are similar exercises. I’m largely looking at the Early Modern period (1500-1700) and the Enlightenment period (1800s), because the devil’s presence is reflected in many narratives of the time.

For example, it can reflect the narrative of a church. John Milton’s Paradise Lost in the dawn of the Enlightenment period, or works by Lord Byron or William Blake, all wrote about the devil as a hero in direct opposition to the popular opinion of the church. This collection of artists are called Romantic Satanists and they fought against religious power over the state.

And so, I’m looking at these current pieces of media, and I’m trying to fit the devil into how they intersect, especially with breaking the fourth wall. I think the narrative technique of breaking the fourth wall is largely reliant, in these pieces of media, on the identities of the characters. The break in the wall enhances the story for the viewer, and it gives insight into maybe where the plot is going or how these characters should be looked at.

Additionally, I’m studying these pieces of media because I’ve been impressed by them. I think they also, each one of them, talk about queerness really interestingly. For a long time when I was growing up, there was not a lot of queer representation. So, if these characters who are queer are looking at me through a screen, we’re making eye contact. It’s another level. It’s another layer for me.

Natasha Beaudoin

What shows like, when you were younger, did you…

Moira Hayes

I feel like there just wasn’t a lot.

Natasha Beaudoin

Was there anything at all?

Moira Hayes

There was like, uh, like, Glee.

Natasha Beaudoin

Okay, Glee. Yeah, yeah.

Moira Hayes

Other than the time, you are set apart from the Old Masters not only by modern technology but also in being a woman. Has gender affected your artistic lens, be that your own, or those of your subjects?

Natasha Beaudoin

Being a woman, I was made hyper aware and conscious about bodies and identities being curated. Whether this is through history or online, through portraits or photographs, the presentation of people has followed the same formula. Say with authenticity, a woman’s perception was all about beauty, and in a lot of the old Renaissance paintings, many of [the women] were fabricated to reflect their inner beauty, rather than their outer depiction. For example, Leonardo da Vinci’s Ginevra de’ Benci, Ginevera face was reconstructed in a way that was more idealized for the fashion of the time, not a faithful likeness. Leonardo also framed her figure with a juniper berry bush to elevate her virtue and chastity, which was meant to signal her moral character.

It’s the same thing with my male models. I group all my models under this umbrella where I’m editing and perceiving them how I see fit, not necessarily how they want [to be] presented, right? So, it’s the same thing with exaggerating the image, or putting my colour filters on them. It’s what I feel best represents them, so I’m applying my own agenda onto them.

Moira Hayes, NATASHA, photography, plexiglas and vinyl, 22 x 30”, 2025.

Materiality plays a large role in your practice, especially post digital printmaking. How does your choice of medium reflect or reinforce your research into the devil, canon and narrative?

Moira Hayes

I like to poke fun at the canon of fine art. I’ve done a lot with the works of the Old Masters. I think that’s something [you and I] have in common: we look at old paintings and think about them a lot.

But I like to buy textbooks or coffee table books and rip the pages out and put vinyl on them, because when I think about them, I’m thinking: ‘okay, this is just a replica of the real thing, it’s just a picture of a precious thing.’ I can find so many books on the Sistine Chapel. I have seven of them, and I can just keep using these images like they’re a cheap print.

And it begs this question, in my mind at least, [that] if I draw on top of these masterpieces, or I put vinyl over top of them, does that mean that I’m inserting myself into the canon? I have shifted largely to working in craft vinyl, because I like that it’s this kitsch medium. But then [you can wonder] is it still kitsch, if I’m putting it on top of a piece from the Sistine Chapel. Is it sacrilegious? Is it hard to take seriously? Is it this? Is that?

I also think while [my work is] still post digital, it’s 100% printmaking, because there’s a matrix that has all the same components. It’s just a different medium. So, in terms of materiality, it’s a lot of me thinking directly about the canon and how to take work like mine, that is often trying to be funny, and push the envelope of what people will accept as fine art.

How does your installation of the work affect the viewer’s connection to your pieces? How do you hope to control or not control this experience for your audience?

Natasha Beaudoin

Well, with the overall installation, I think about the spatial separation between the images and canvases that are responding to, or trying to mimic, screens—like individual screens, or individual photographs, or placement of monitors.

[This is] a reference back to how the photos were originally taken. They’re taken with my phone really small, then they’re super large, and become drawings or paintings on canvases. And a lot of times when people experience them, the pieces are a lot bigger than they were expecting. People say, ‘Oh, it’s funny, something that is so tiny, like my phone which is two inches by four inches, is then put into a larger scale, like 20 by 30 inches.

And then also how light is experienced, and how I capture light physically to put light into the canvas. For example, the AB crystals I put in. A lot of the time people think that’s led lights, which actually works in my favor. And then it becomes a play on what’s seen on Instagram versus in real life, because I post my paintings and their progression online, but seeing them in person shifts the experience.

Alright, final question:

Natasha Beaudoin, Moira ɐɹᴉoꟽ M̸̟̟͍̀́̚o̸̺͇͕̕͝͠i̸̪̘̠͆̈́͝ŕ̴͓̝̼̓̕a̴̢̟͙̒͑͝ ,Oil on Canvas and Mylar, 24×48, 2025.

What is a critique of your work that you could easily debunk?

Moira Hayes

That’s hard. I feel like a lot of people just don’t get the work.

Natasha Beaudoin

Yeah, I feel that.

Moira Hayes

I think that if you don’t think it’s funny, maybe you’ll think another piece of mine is funny, and if you just see [my art] as me being silly, well, I am being silly and that’s part of it. So I guess there’s no debunking it.

I think it’s just about your attitude and how long you’ve been in the institution. That’s, unfortunately, a big part of it. I have received, in the past, really weird critiques, and they usually come from a lack of understanding my viewpoint. I think being outside of the institution for so long and then going back to school has informed quite a bit of how I make work.

Natasha Beaudoin

Yeah, I think it’s also [they’re] not taking something silly seriously.

Moira Hayes

Yeah, they don’t know where to put it. Even something small like my business cards say, ‘Moira Hayes: Making Work that Confuses My Parents since 1996.’

No shade to my parents, but I showed my parents my recent work, like, when I first moved back to London [after my undergrad] and they would go, “Oh, that’s nice.” They don’t know what to do, you know? They’re used to looking at pieces like paintings that are so beautifully rendered, like yours.

Natasha Beaudoin

But at the same time, my parents don’t like any of my work. They want something really abstract, like hotel art.

Moira Hayes

Oh man, IKEA art, yeah.

Natasha Beaudoin

So, they don’t like mine. They don’t get it either. Like, why? They ask me, “Why do you paint these people?”

Moira Hayes

Yeah, why do you do it?

Natasha Beaudoin

Well …

Moira Hayes

“Why wouldn’t I?”

Natasha Beaudoin

Yeah. Because it’s what I like.

Moira Hayes

So, what’s a piece of criticism that you’ve heard more than once—and you have probably answered the question— that you could easily debunk?

Natasha Beaudoin

I think it’s two things. One is what it’s even about. What confuses a lot of people is that my art is very surface level. What you see is what you get. It doesn’t have any grander meaning behind it. It’s a picture of my friends. We’re probably camping. I photographed them in some manner.And that’s it.

I feel a lot of the time, art is expected to have this grander opus. My art is not political at all. It’s not sophisticated in the subject matter, but it’s a subversion, because my way of painting is very sophisticated with its realism.

And that’s another point, another critique, is that it’s ‘just’ a pretty picture. And it’s like, yeah. I would hope so! They’re treating it as a bad thing. The whole reason why you look at art is because you like it. It’s interesting. It catches your eye, and then the subject matter, later, goes on with it.

We’re humans. We like pretty colours. God forbid something catches your eye. I think that’s what it should be like. So, I just find it very silly: this need for a great heavy digestive breakdown. Like c’mon, just enjoy the painting.

Moira Hayes

I think that’s something that’s very similar between our work and I think it has a lot to do with the time period that we’re both looking at. What’s happening now? Which isn’t to say that other people aren’t looking, but I feel like we’re both looking at it with a lens of, “This is so silly!”

Natasha Beaudoin

Yeah. It becomes a nihilistic way of perceiving the world, but a very positive viewpoint as well. Very Gen Zed.

Moira Hayes

Gen Zed. Gen Zee?

Natasha Beaudoin

Actually, sitting here reminds me of when you’re in grade eight and you have a school project to do and you’re like, allowed to work on it outside.

Moira Hayes

Yeah, yeah. I know exactly what you’re talking about.

Natasha Beaudoin

Well, all right, nice.

Moira Hayes

Nice.

Natasha Beaudoin

And we can hear each of the birds.

Moira Hayes

Yeah, we’ll talk about the birds for sure. We can do like a little list of them.

Natasha Beaudoin

Yeah, actually, yeah. Hold up.

Moira Hayes

Pull up Merlin? [Merlin Bird ID app]

Natasha Beaudoin

How did you know? Okay, speak birds! No. The river is too loud.

Moira Hayes

That’s alright. We know they’re here.

The Digital Fourth Wall

Natasha Beaudoin | Moira Hayes

🗓️ June 26 – July 10, 2025

☕️ Reception: Thursday, June 26 from 5:30-7pm

📍 Cohen Commons, John Labatt Visual Arts Centre

🚗 Free parking in Middlesex Lot [G] from 5PM onwards

Summer Gallery Hours

Monday-Friday from 12-5PM

You must be logged in to post a comment.